Gorge version

by Matt Souders & Mike Godsey

You may have noticed that the wind and weather has gone a bit bonkers at times this year for much of the west coast. You’re not wrong – the data backs up your impression. And, no, it is not Global Weirding, at least not directly.

This year the Gorge had a very mild winter that had daffodil bulbs budding in late February and then had snow on the ground for almost a month in March. Then it had a crazy long May heatwave. Then unending mid 30’s wind in June. And then a long period of weird clouds and sporadic wind in July.

All this while, in the San Francisco Bay Area, there’ve been long periods of eddies and southerly winds along the Bay Area coast with the beloved NW winds of the North Pacific High AWOL.

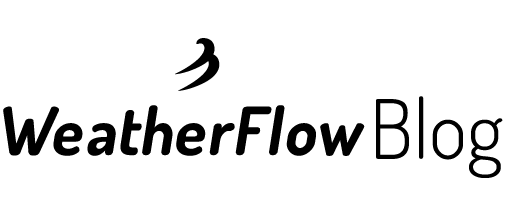

So what is behind all this Gorge and San Francisco weirdness? Basically, the direct cause is the atypical shape, size and location of the North Pacific High. And that, in turn, was impacted by:

- El-Nino induced north Pacific ocean warming encouraging the northward growth of the North Pacific High

- El-Nino causing the average storm track to drop southward so storms more frequently distorted the shape of the NPH, often breaking its northern and eastern flanks off and pushing them into the interior Northwest helping eastern Gorge winds.

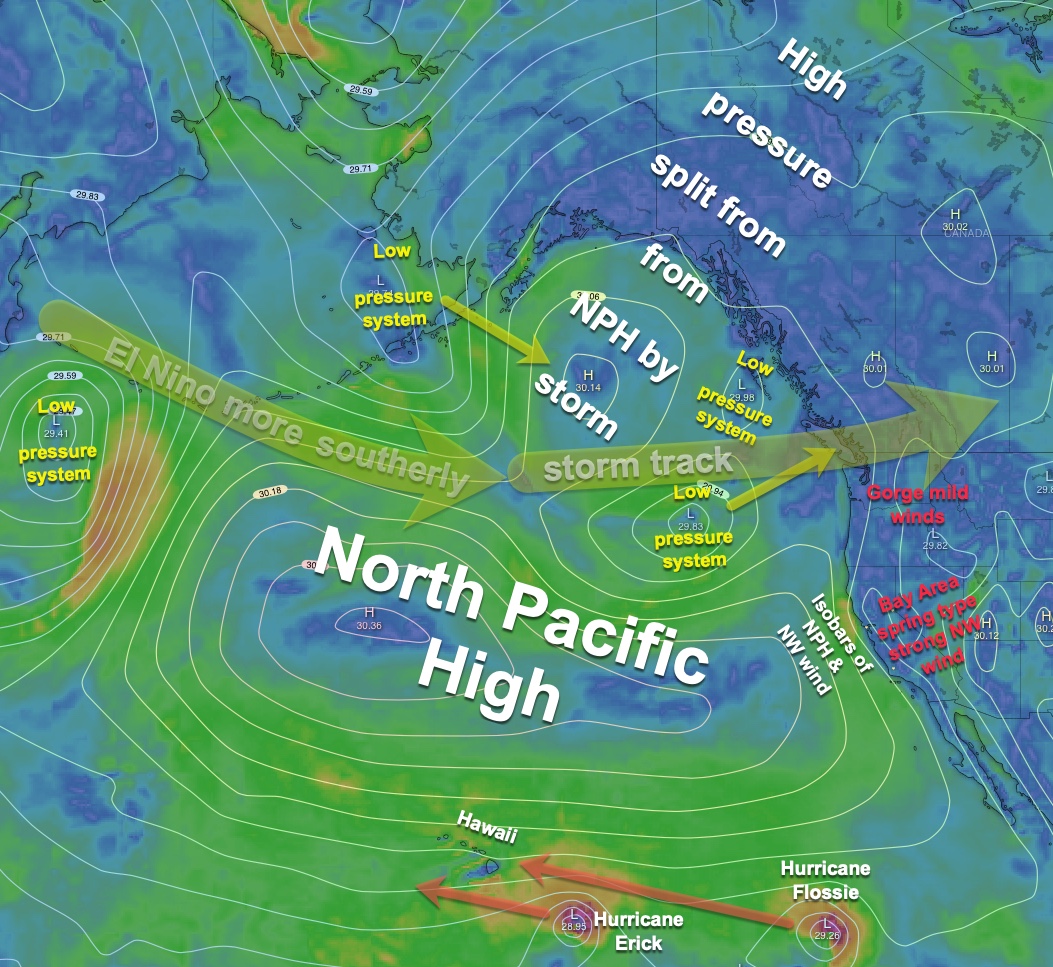

- A strong warm phase to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) which helped warm the Alaskan coastal waters and, from there, the entire Pacific coast cold water current.

- One of the warmest seasons on record in the Arctic Ocean (common during warm PDO/El Nino, but made worse by the recent Arctic warming).

- The presence of higher pressure over the Pacific Northwest and the warmer coastal shelf waters from the Alaskan current are thinning the marine layer and this, in turn, is causing winds in the Corridor to be more unstable, to blow solidly for shorter intervals many days.

- The El Nino is also creating an opening for unusually sharp upper-level troughs to pass through the Gorge region which keeps temperatures sometimes cooler than normal during early summer and changes the nature of marine layer clouds in the Corridor, giving them more height and picking them up off the river which makes the wind more up and down. This also has meant stronger winds aloft which helps sites out east. On the downside, though, with more upper-level NW winds behind troughs, traditionally good launch sites out east like Maryhill and The Wall on the WA side are seeing wind shadows mixed with WNW blasts as the wind in the area is more WNW rather than the more WSW in past years. Meanwhile the change sometimes benefits the Oregon side Rufus launch.

Let’s look at the North Pacific High this year versus the past decades.

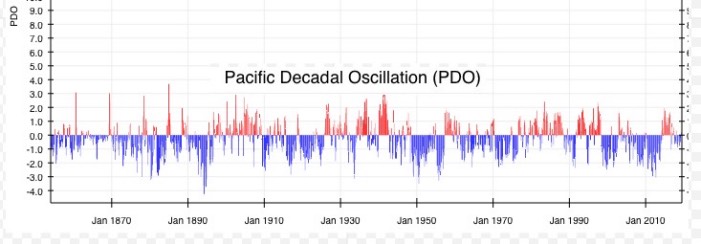

First, in this image let’s look at the average shape and location of the North Pacific High over the period from 1967 to 2010. (I picked that period because the North Pacific High was very predictable back then while in more recent years it has a become way more variable for reasons we will get to later.)

Notice how the North Pacific High is a small oval and way to the south during the winter.

Then, starting in March, the oval NPH expands and is

centered west of Baja. This is why the winds at the Punta San Carlos wave sailing mecca begin to build in March.

Then, as Spring turns to Summer, the NPH’s average location moves northward. In May, for example, it’s typically centered west of Southern California, which turns winds NW along the Central and Southern coasts.

Then the NPH centers off of the San Francisco Bay Area and the NW winds peak after each passing storm. In July, it centers west of the Gorge where it works with the low pressure in the Columbia Basin to make the Gorge winds blow very reliably, especially in the Corridor.

Finally, in September, it shrinks and begins moving southward and west coast westerly winds fade.

Remember these are average locations and each time an upper trough/surface low pressure passes to the north the NPH moves southward.

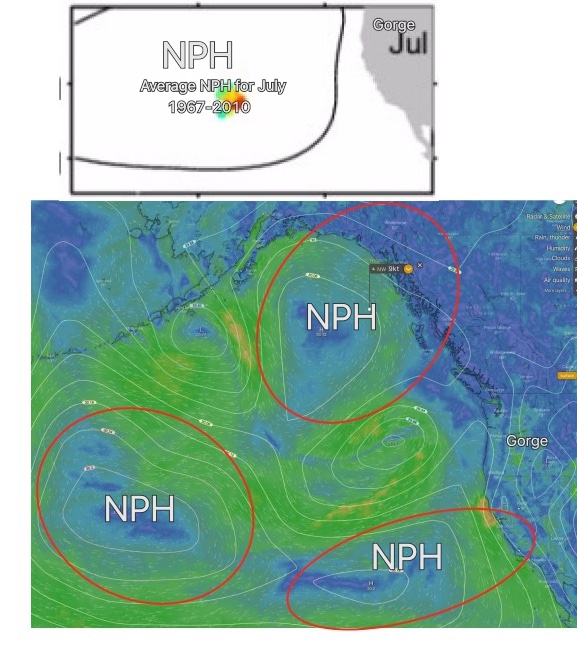

Now looking at the second image compare the July Average North Pacific High and compare it to today Thursday, Aug. 1, 2019. Wow, quite a variation from the norm!

Clearly, the North Pacific High is much larger and fragmented by all the low-pressure systems following a southerly storm track. Especially note how the NPH has been bumped away from the Gorge.

Every few years, the El Nino-Southern Oscillation – a warming of tropical Pacific sea-surface temperatures linked to a slowing or even reversal of the normally easterly trade winds – begins.

El Nino is tied to a host of changes to the normal climate of the west coast. If you live in California you know that a strong El Nino brought more rain than normal to California this winter.

However, El Nino’s effects in the summer are not as well understood, but, this year, we are seeing some strange ones.

El Nino increases westerly winds south of the North Pacific High. Those west winds have often been stretching the North Pacific High north and south.

That is why the forecast has sometimes noted that the NPH stretched up to the Gulf of Alaska or even over Alaska itself.

Those El Nino westerly winds have sometimes crippled the southern flank of the North Pacific High, disrupting Hawaii’s trade winds.

This last graphic shows what the North Pacific looked like in late July. This image shows all the major players in the weird wind pattern we have often seen this spring and summer.

So what does the future hold for the Gorge windwise? The El-Nino will subside soon and the PDO will gradually move towards a cooling phase. However all evidence suggests that El-Ninos are getting stronger in recent decades. Plus the overall warming of the Arctic is going to be an issue. Even in a cool PDO, a warm arctic may mean we struggle to get the deep marine layer influences we once did, as coastal waters may be just warm enough to make it difficult to keep those marine air masses stable.