by Matt Souders & Mike Godsey

At this point, you are probably wondering about the thick haze every morning that has plagued the Gorge and much of the Pacific Northwest. It barely has a hint of the typical brownish color of wildfire smoke nor does it have the smell of smoke. And unlike smoke, it largely burns back each afternoon.

There are three factors coming together to keep the interior west so hazy despite the heat – the persistent upper-ridge anchored over the Columbia Basin, the monsoonal moisture pouring in from the coastal waters off Southern California and Baja, and the wildfires that continue to burn in the interior California, Nevada and southern Oregon.

I, Matt, actually fielded a question regarding my use of the term ‘monsoonal low’ to describe the surface pressure pattern in the Gorge. I never properly defined the Southwest US monsoon in my forecasts, but, in short, it occurs when moisture, usually from the subtropical Eastern Pacific gets pulled north into CA and the Four Corners states by persistent low pressure caused by the extreme desert heat, causing more thunderstorms to pop up, especially near high terrain

Monsoonal moisture usually does not affect the Gorge, but, as you’ve probably noticed, it’s been a hot, dry summer and the thermal low has been stronger than normal as a result. With a persistent upper-ridge in place, the increased moisture – mostly 3-5 thousand feet up – has nowhere to go and gets stuck swirling around between the Rockies and Cascades.

But moisture alone doesn’t quite explain the haze. The missing ingredient is the smoke I mentioned earlier. To make a cloud, you need water vapor, a little bit of lift (to force the air to cool and the water vapor to condense), and some small, solid particles suspended in the air that the water can stick to.

Without those particles, water vapor can’t condense and clouds can’t form.

Meanwhile, there is a thin smoke layer much further aloft that sometimes gives sunshine a slightly brownish color. But that smoke has been way way aloft so you are not looking sideways through miles of smoke so no brown haze.

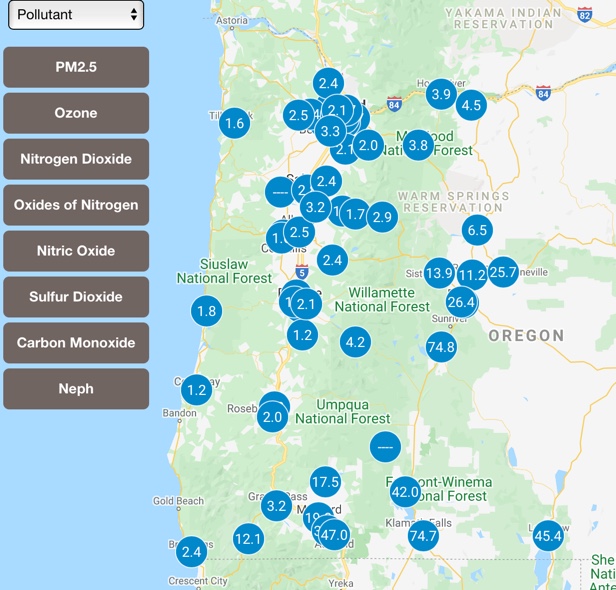

Weirdly, throughout this haze event, the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality has been reporting fairly good air quality despite all the haze. This is because air quality is a measure of the 8 variables shown in this graphic.

And our surface haze being mostly water vapor it is not considered a pollutant.

And the smoke from the California Dixie fire is way aloft so it is not being detected by the surface sensors.

But notice the poor air quality being reported in the area of the fires in southern Oregon.